Why Russia may control Turkey’s Nuclear Energy for the next 80 years

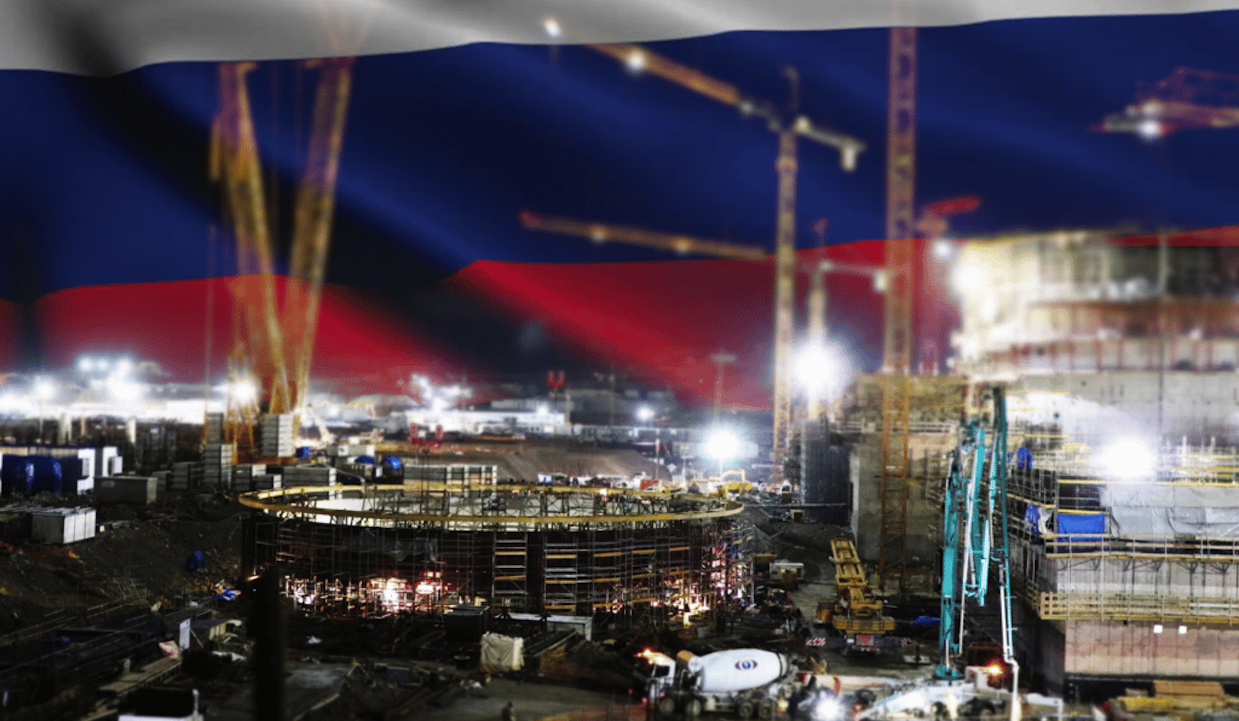

On the cover image an inner compartment shell is being installed at the first unit of the Akkuyu nuclear power plant in January 2022 in Turkey. The Akkuyu plant will include four Russian-designed VVER-1200 reactors built, owned, and operated by Rosatom, Russia’s state-controlled nuclear energy company. (Image Akkuyu Nuclear / François Diaz-Maurin)

All links to Gospa News articles have been added aftermath for relevance to the topics covered

by Ali Alkis, Valeriia Gergiieva – originally published on The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

In May 2023, Turkey’s first nuclear reactor will receive its first fresh fuel. The Akkuyu nuclear power plant—which includes four units of Russian-designed VVER-1200 reactors—is expected to be fully operational by 2026. But this progress is happening amid growing concerns over the stability of Turkish-Russian nuclear cooperation.

Turkey already imports natural gas from Russia, and the nuclear agreement would create more dependence on Russia—for nuclear technology, nuclear fuel, and training of staff to operate the nuclear power plant. This comes with no small amount of risk; Russia has shown it can use energy dependence as a tool in political bargaining.

A long journey

Ankara’s quest for nuclear energy dates to the late 1950s. The motivation for this nearly six-decade-long journey has been associated with the development of Turkey in terms of economic growth and energy security. More important, development of nuclear power has been seen as a symbol of Turkey’s modernization. Turkey has certainly modernized over the last six decades but during that time has failed to develop a working nuclear power reactor for a variety of reasons. During the 1960s, Turkey’s financial capabilities—given a gross domestic product that was under $20 billion—were considered insufficient to support a nuclear power program. Initial interest and plans were halted following military coups—in 1971 and in 1980—with subsequent political and economic instability.

Turkey’s third attempt came in the 1980s when the Turkish economy had grown to a GDP of over $60 billion, above the $50 billion generally accepted as the threshold for nuclear power development. At that time, Turkey changed its strategy to the build, operate, and transfer financial model, in which a vendor would pay the construction costs, recoup its expenses by operating the plant for a specific time, and then transfer the plant to Turkish ownership in exchange for a percentage of future profits. These plans were halted after Turkey insisted on 100 percent foreign financing and the 1986 Chernobyl disaster increased domestic opposition to nuclear power. Concernsabout Turkey’s role in the Pakistani nuclear weapons program, in which Turkey was suspected of helping to transfer nuclear material, also contributed to the failure of this third attempt.

For its fourth attempt, in 1994, Turkey issued an international tender for a turnkey project. However, the tender was postponed several times due to technical and economic reasons while it was also sometimes linked to corruption claims. As a result, a purchase guarantee could not be issued, and the fourth attempt was abandoned in 2000.

Russia as the only option

At the end of 2002, Turkey initiated its fifth attempt, again issuing an international tender. This time, the move was partly motivated by concerns over Turkey’s dependence on Russian gas. But the project received only one bid—from Rosatom, Russia’s state-controlled nuclear energy company—which was considered too expensive, so the last effort with the build-own-transfer approach failed this time again.

RELATED: Russian actions at Zaporizhzhia show need for better legal protections of nuclear installations

In 2008, after five failures, Turkey again shifted strategy, now toward an intergovernmental agreement that would allow vendors to sidestep competition rules and enable vendors to own the plant. As a result, in 2010, Turkey and Russia signed an agreement for nuclear cooperation.

As part of the agreement, Rosatom will be authorized to build, own, and operate the Akkuyu nuclear power plant with 60 years of service life—plus a possible 20-year extension—until its decommissioning, which Rosatom will also be responsible for. Rosatom will also supply the fuel and manage the waste generated while helping Turkey build the necessary human capital. In exchange for all these services, Turkey will supply the Akkuyu site free of charge and commit to buying the electricity generated for 15 years at a fixed rate of 12.35 cents of a dollar per kilowatt-hour.

Given the costs for the construction, operation, and maintenance of the plant, as well as for the management and transport of the waste, this was considered “an economically well-negotiated agreement” by nuclear energy policy experts. In short, it was a good deal for Turkey.

Exaggerated proliferation concerns

As soon as the agreement was signed, Turkey started to be seen as a possible nuclear proliferation front. Analysts even estimated that, among the nearly 30 countries interested in developing nuclear power, Turkey was the most likely to divert nuclear material to develop nuclear weapons, divert civilian nuclear knowledge and technology for military purposes, and have its nuclear material stolen by non-state actors.

These concerns are not new. Some attributed Turkey’s previous failures to develop nuclear power partly to concerns by the United States and other Western countries over proliferation risks and Turkey’s close relations with Pakistan—known for its proliferation activities since the 1970s. But these concerns are not solidly grounded. The Turkish nuclear energy program is based on the build-own-operate approach, which by definition calls for a third party—Rosatom—to run and own the plant. Moreover, the fuel guarantee and take-back arrangements leave Turkey with no direct access to nuclear material and therefore no possibility to divert such material for non-peaceful uses.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, therefore, Turkey’s international agreements—combined with its non-proliferation commitments—make its nuclear energy program probably more proliferation-resistant than any other country currently developing nuclear power.

The (real) risks posed by the Russian deal

While the build-own-operate approach has helped Turkey overcome some challenges—by halting a decades-long series of failed attempts and offering some guarantee that its nuclear energy program serves peaceful purposes—it has also created new ones. In defining its strategy, Turkey used energy security as a justification for its nuclear power program, which, it claimed, would help decrease its dependence on natural gas imports from Russia and Iran. But the model used to develop the Akkuyu nuclear power plant makes Turkey heavily dependent on Russian technology. With Moscow having a record of using its energy assets for coercion, the future of the nuclear cooperation between Turkey and Russia may be the real issue.

From an energy security perspective, the nuclear deal does not solve Turkey’s dependence on Russia’s natural gas, but rather adds a second dependence on nuclear technology. Turkey will now no longer depend on Gazprom but also on Rosatom—two Russian state-controlled companies—for nearly every step of its nuclear power program—from the construction and operation of the plant to the management of the entire nuclear fuel cycle.

RELATED: Why the world must protect nuclear reactors from military attacks. Now.

Rosatom may also try to finish the project on time to avoid having to pay penalties. As it turns out, the plant’s construction is on schedule—a very rare situation in such mega projects. As a result, Rosatom could be tempted to ignore or overlook minor problems during the construction of the four reactors. This adds an additional burden on a nascent Turkish regulatory authority whose regulators are currently being trained—in Russia. Regulators will therefore require very detailed legislation for commissioning, operation, maintenance, and decommissioning steps to ensure independent verification of all relevant procedures.

But—to further exacerbate an already unbalanced cooperation arrangement—the intergovernmental agreement requires Rosatom to assist Turkey in drafting its regulatory framework, which could lead to a conflict of interest and even the possibility of “regulatory capture,” in which the regulated entity manipulates lawmakers and regulators to put private interests ahead of those of the general public.

Turkey’s biggest—and most immediate–human resource challenge may be to establish and support a regulatory agency that can oversee the power plant during its construction and operation. Turkey has yet to gain experience in civilian nuclear power regulation, and there is no experience with regulating these new reactors outside Russia. Very few experts therefore have specific knowledge about the VVER-1200 reactor design. Moreover, all the experts in the VVER-1200 design are either Russian or have a close relationship with Rosatom, resulting in another potential conflict of interest.

Risks can be mitigated

Although Turkey’s dependence on Russia for its nuclear energy program has deep implications, it is still possible for Turkey to mitigate these risks, if it takes the right steps in the future. These include diversifying vendors for future plants and establishing closer cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for regulatory services. For instance, Turkey has already started talks with US vendors for small nuclear reactors. There are also plans for a second nuclear power plant, for which the Korea Electric Power Corporation intends to build up to four reactors.

These steps toward increasing the energy security of Turkey could be reinforced with regulatory developments with the help of the IAEA. For instance, in 2022, the agency carried out an “integrated regulatory review service mission” to establish and strengthen Turkey’s regulatory framework.

It is only through such steps that Turkey will fully enjoy the benefits of the peaceful uses of nuclear technology without creating new risks and affecting its energy security.

By Ali Alkis, Valeriia Gergiieva – originally published on The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists – February 21, 2023

Ali Alkis is the World Institute for Nuclear Security Ambassador to Turkey and a Ph.D. candidate at Hacettepe University in in Ankara, Turkey. Alkis is one of the few male members of the Black Sea Women in Nuclear Network and has been recently appointed as the Gender Champion at the Odesa Center for Nonproliferation. His research interests are nuclear security, non-proliferation, and nuclear terrorism, as well as Turkish nuclear and foreign policies.

Valeriia Gergiieva is a visiting research fellow at the Institut für Friedensforschung und Sicherheitspolitik (IFSH) at the University of Hamburg, Germany, and a research fellow at the Odesa Center for Nonproliferation. In 2021, she received her Ph.D. in political science from the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. She is a member of the US-Black Sea Nonproliferation Professional Exchange and the Black Sea Women in Nuclear Network.

Un pensiero su “Why Russia may control Turkey’s Nuclear Energy for the next 80 years”